Who says English fizz doesn’t need an identity?

We asked the consumer, and here are our findings.

“It’s all Bo**ocks – why don’t they ask English sparkling wine producers what they think.” Perhaps this is inevitable when consumer insights and brand marketing meet an emerging craft industry.

That was one comment left on Harpers' write-up of Pull’s English wine event. Pull was presenting the findings of our survey of the buying habits and attitudes of British wine drinkers.

Like Champagne – but different

English wine is a great success story. After a hesitant start in the seventies and eighties, English wine is now on a great surge of confidence with a best ever vintage in prospect for 2018 and production likely to hit 6m bottles – up nearly 50% on 2017. English wine has largely found its feet over the last decade largely due to the discovery that wines produced from the Champagne ‘holy trinity’ grapes of Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay, and using the ‘méthode champenoise’ bottle fermented approach, could be just as fine as the best Champagnes. Grapes ripen slowly in the knife-edge English climate, producing wine that it often similar to Champagne, but with its own distinct complex character.

Wine production is booming in Britain and today 75% of English wine production is méthode champenoise sparkling wine. Every year, substantial new acreage is planted, and even the big Champagne brands are investing in English vineyards.

This is a very encouraging scene. However, as a big fan of English sparkling wine, and a big believer in the power of brand, I have long felt that this product has an identity problem.

As such we postulated in a blog last year that English sparkling wine would be better understood by the consumer if it had a consistent or core identity. With a premium price (typically from £20-£50 a bottle) it is pretty much in line with the price of its more prominent cousin Champagne – a true luxury product with an image to match.

As we pointed out in our blog, all previous attempts at creating a name for English fizz have fallen by the wayside. Merrett, Britagne, Bulari, Sussex Sparkling (not sure if this has been seriously proposed for all English fizz.) have all been proposed, but failed to gain traction beyond their sponsor. We don’t think it is hard to see why. These have typically been put forward by individual vineyards, often registered by them, and then offered to the rest of the industry. We don’t think this approach is ever going to work for two reasons. Firstly the ‘not invented here’ syndrome, but perhaps more importantly, because coming up with a name isn’t creating a brand.

Research

As an agency delivering brand transformation we were – and still are – convinced that this world class product would gain traction at home and overseas in a much stronger way if all the individual brands could share a common umbrella identity like Champagne and Prosecco does. Our favourite projects consist of putting challenger brands on the global map (Andertons Music Co.) (Gocycle Electric Bike) and we can’t think of a better challenger brand than English wine.

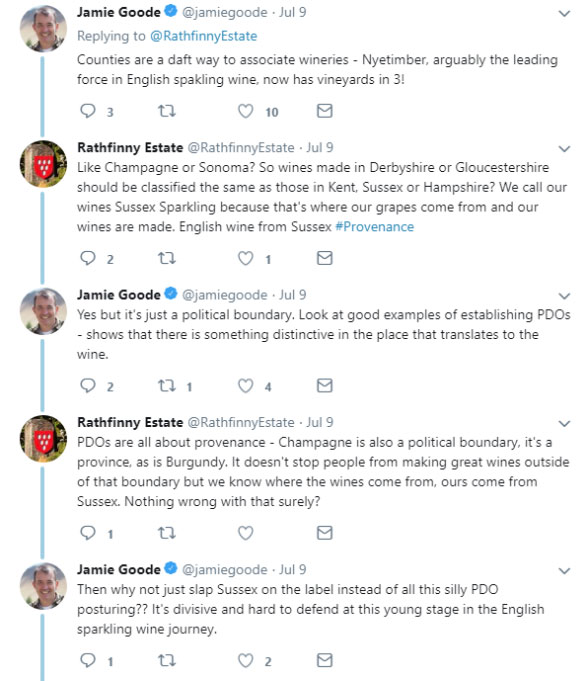

However, we knew that we would get nowhere without new information. We monitored and engaged in some debate online about branding English fizz.

Clearly there were as many views on branding English wine as there were producers, but no-one was talking about the consumer - how they navigated the world of wine, and how they perceived English wine. We doubted that the industry would listen to the theory of branding English sparkling wine from an outside party – but what about feedback from the consumer? Surely this would prove our hypothesis. It did. But its not the end of the story.

Our research samples size was 1,100, and we recruited proportionately across the UK & Northern Ireland. So, we are pretty confident that our sample was representative of native wine drinkers.

Segmentation

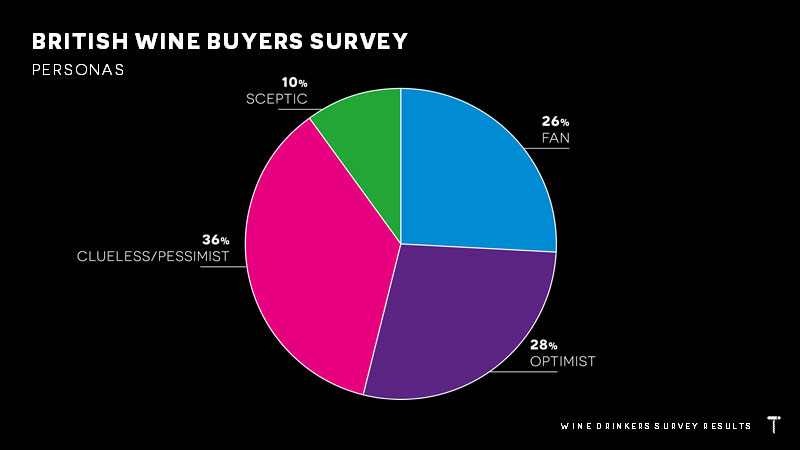

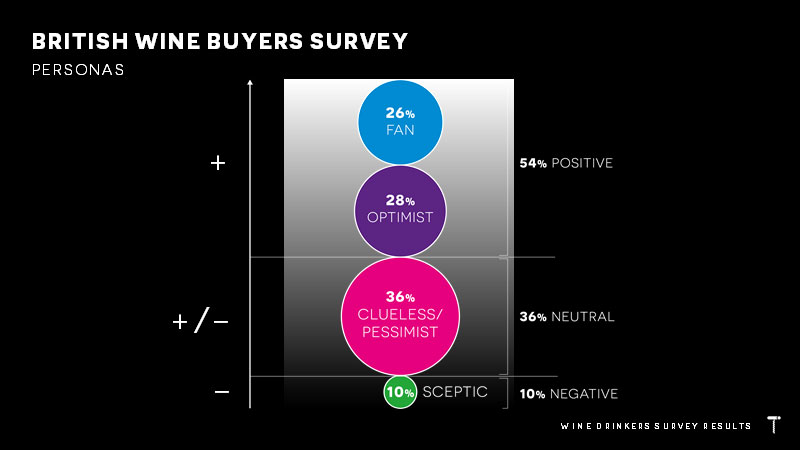

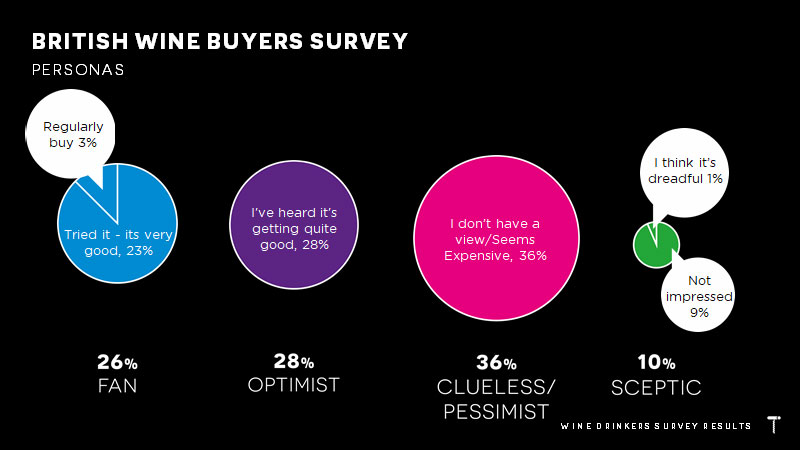

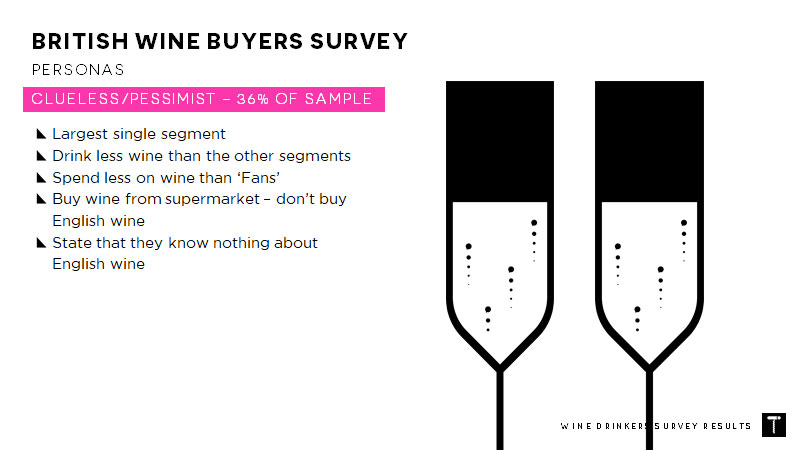

The research looked at all aspect of our respondent’s approach to selecting and buying wine. However, as our special interest was English wine, we used the respondents’ knowledge and attitudes to English wine to identify 4 Personas: We called these: ‘Fans’, ‘Optimists’, ‘Clueless/Pessimists’ and ‘Sceptics’.

From this we can derive a general level of sentiment: It seems that the majority of British wine buyers have a broadly positive sentiment towards English wine, with 36% probably defined by not having a sentiment on the basis that they have never tried it, and 10% who might be considered to have a negative sentiment.

These consumer sets were derived from the following attitudes among our respondents.

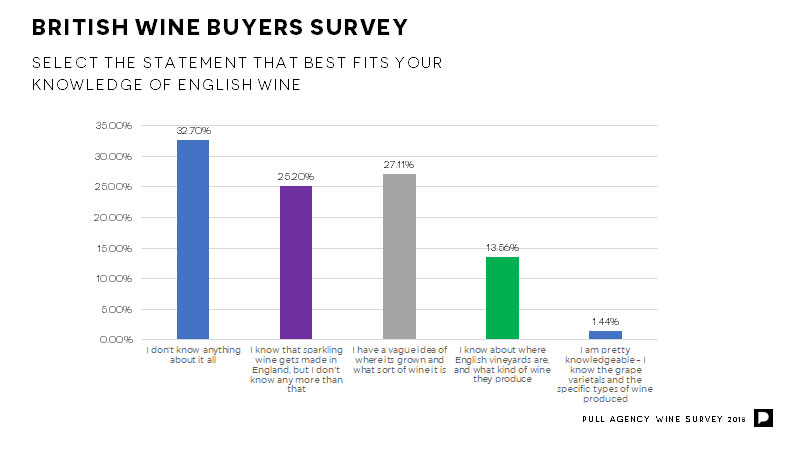

In terms of knowledge, it seems that the majority don’t have much understanding of English wine with 85% having ‘not a clue’ or ‘only the vaguest idea’.

I think this was a bit of a surprise to our wine industry event audience – some even seemed to be in denial. Our view is that its better to know and develop strategies accordingly. To quote Julia Trustram Eve from WineGB. “I hate the idea that we need to educate the wine-buying public – we just need to make English wine more appealing”

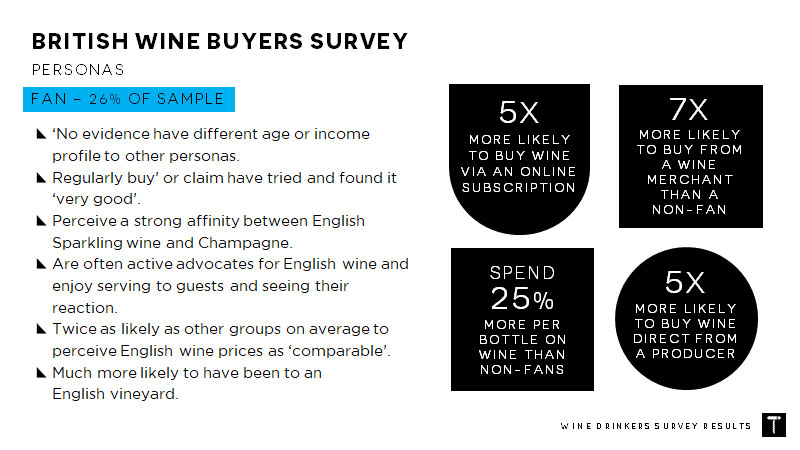

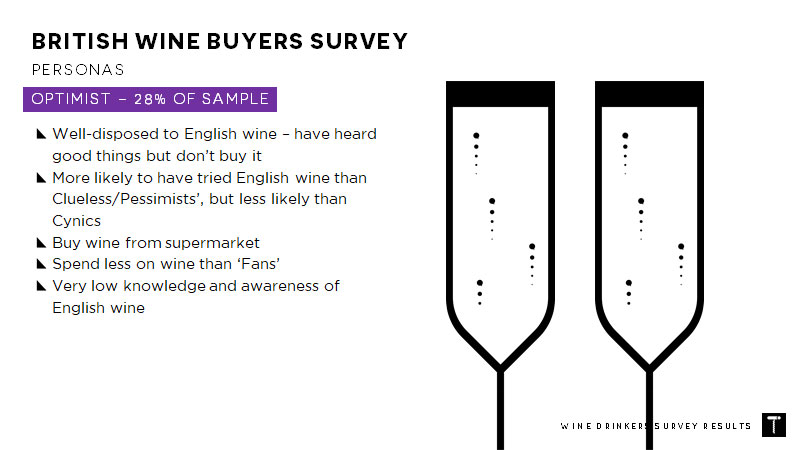

These were the key characteristics of the different segment personas:

Champagne and English sparkling wine

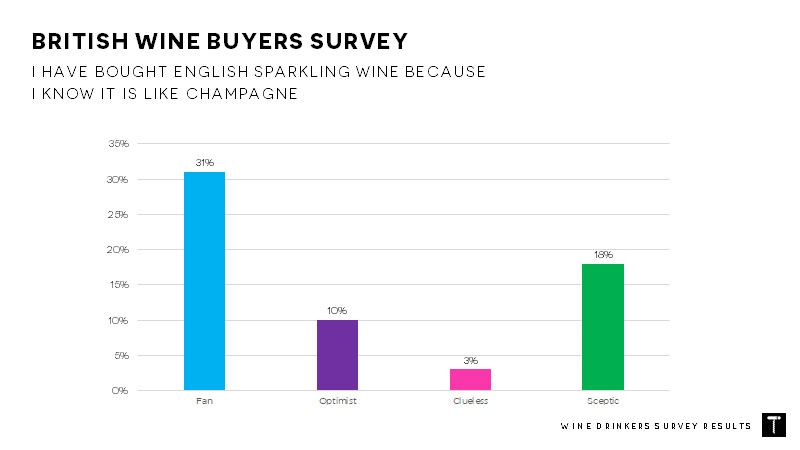

We were particularly interested in the relationship between Champagne and English sparkling wine in the consumer’s mind. And our findings confirmed a feeling that this is what is at the heart of the marketing dilemma for English fizz.

What we found was that nearly half the people who have bought English wine did so because they knew it was comparable to Champagne. This seems fundamental, and relates closely to what we also learnt about the wine buyer’s purchase journey.

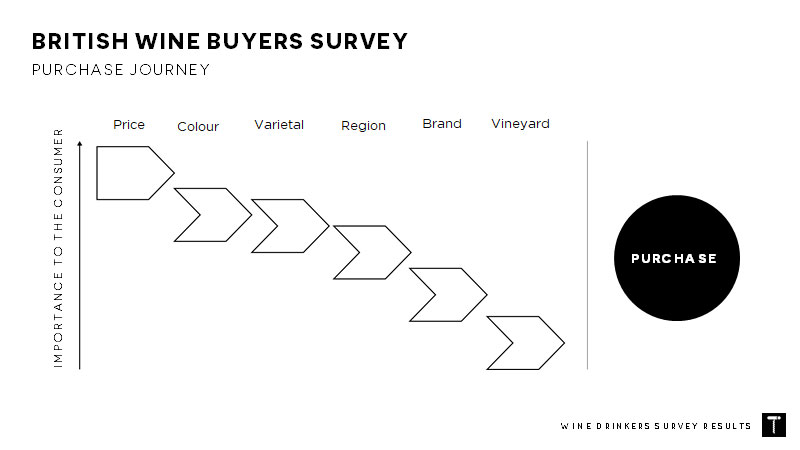

We asked respondents to rank buying factors by their importance as criteria for selecting wine. Unsurprisingly (we know from other research that UK wine buyers are particularly price sensitive) price came first and vineyard last. Again, this result was uncomfortable news for some vineyards. I can understand why it seems counter-intuitive to them: “But people who buy my wine always come back for more.” But as we said in our commentary about the relationship between English fizz and Champagne – there are those that know and those that don’t. Those that don’t need some clues and cues.

Let’s bring this to the ‘decisive moment’ - in-store. Imagine a bottle of English fizz has caught the attention of one of the ‘clueless’ majority. Perhaps it’s on promotion. The shopper picks up the bottle wondering what it is. Three recognisable things run through her mind: Champagne, Prosecco and Cava. It looks related, but what is it? If it’s like Cava or Prosecco it looks expensive. Is it like Champagne? If so might be worth a punt.

The issue is that nothing about the packaging really gives her a clue beyond the fact that it’s sparkling. 50% of our survey respondents couldn’t recognise a single English sparkling wine brand even when shown some. So, unless she is in the 1.5% cognoscenti group, she probably won’t recognise the brand or vineyard. A view quite often expressed within the industry is that English sparkling wine name in itself is more than enough to define the product. Firstly, it is clearly a descriptor and not a name. Secondly, very few English fizz producers actually use this descriptor on the bottle.

Patriotic wine buying

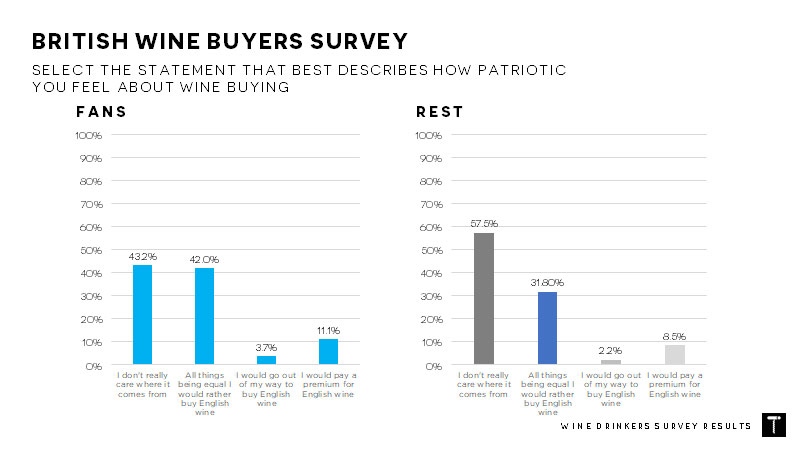

Among the curious advice we received prior to running our survey was one piece about patriotism. “For God’s sake don’t bring that into it. There’s no reason we should be going down that route”. Another example methinks of confusing consumer insight (the research) with marketing strategy (what you do about it).

So we did ask. And what did we find? That for fans – all things being equal (price, quality etc.) – they would rather buy English wine. Even 32% of non-Fans thought the same thing. In fact 11% of fans and 8.5% of non-Fans said that they would even pay a premium for it.

Have you ever bought wine in a French supermarket? Wine is presented by regions of France – Bordeaux, Burgundy, Côtes du Rhone etc. And then there is a little section for wines from the rest of the world. All things being equal – French wine buyers – and Spanish, and Swiss, and Australian support their local wine producers. Even in often over-deferential Britain it seems reasonable to expect some of this reaction to home-produced wines.

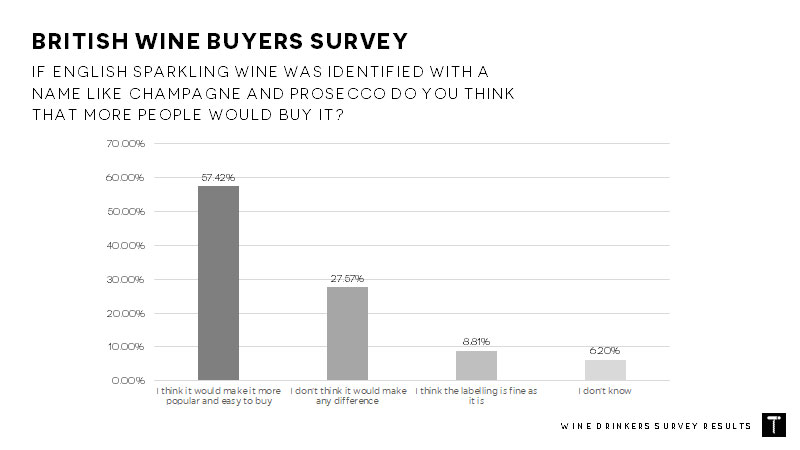

Lastly, we asked respondents their opinion on the big controversy: ‘If English sparkling wine was identified with a name like Champagne or Prosecco do you think that more people would buy it’?

I think this was the question and answer that our English wine expert didn’t like. What he was saying seemed to be: “Huh consumers – what do they know?” “It’s the winegrowers who are equipped to answer that one”. But I would ask him the simple question – who’s doing the buying here? Consumers aren’t going to tell us how to market English wine, but if 60% think that English fizz would be more accessible if it had a clear identity, and only 9% think that the current labelling is helpful, does it make sense to respond by saying that consumers were the wrong people to ask?

So where are we now?

Two conversations with folks in the English wine industry stuck in my mind. One was a leading winemaker who was very concerned about having a ‘manufactured’ name stuck on them; presumably something like ‘Britagne’. We get that. Most key wine signposts have been born out of the very soil – or ‘terroir’ ‘of the region: Bordeaux, Burgundy, Rioja, Napa Valley. Naturally, if English wine is to use something as a name it must come via the same sort of root. This we heartily agree with. But as an agency used to uncovering (sometimes unlikely or buried) authentic provenance in building our clients’ brands we are used to this. In fact, we have some fantastic ideas for the English sparkling wine industry. These will never see the light of day though if there is no mood for collaboration over identity. We have no doubt that an identity can successfully be created and communicated, but it obviously won’t happen without a willingness to make it happen.

The other conversation that stuck in my mind was one I had was with one of the larger English wine producers and went something like this: “Well there are English wine brands who have built up a strong following. They aren’t going to want to overlay their hard-earned recognition with something else. On the other hand, the small producers and the distributors will want it – but they can’t afford to fund anything. Something will emerge in the way of a name – in the end the consumer will call it something. In the meantime, we think our priority should be to focus on making a great quality product.”

This is understandable, but also tragic in our view. It’s true – left to its own devices, the market will sort itself out – that’s what markets do. But let’s imagine the two scenarios:

Firstly, English wine is left to sort itself out. Yes, a name will emerge. In the absence of an industry initiative to create a core identity, I would put money on what it is. It’s ‘English fizz’. Why that? Well because when distributors, merchants and retailers want to reach for a collective noun, that’s what they use. It has taken 100 years of consistent, co-ordinated and clever collaboration for Champagne to reach the premium luxury brand status that it has today. How long will it take ‘English fizz’ without a crafted identity, consistent marketing and few clues about the content of a bottle?

Then imagine that the industry agrees what is and isn’t English sparkling wine (actually, this has been done, but we couldn’t find any one party in the industry who could tell us exactly how it was being implemented), creates a market positioning for it that juxtaposes it with competing wine types, agrees an identity (not just a name – it could include a unique bottle, unique foiling, a shared additional label on the bottle and complimentary accessories – unique glasses for instance). Then agree collaborations with matching products and services, sponsorships etc. These wouldn’t be done on behalf of the meta-brand – but just carried out by the individual brands and vineyards to create a similar perception across those brands. The consumer would ‘get it’ faster, and trial rates would be much higher. Acreage is going down to vines in England at a record level and production set to at least double. That amounts to 10m bottles. Britain consumes 30m bottles of Champagne, so this suggests a sizeable move from Champagne to English fizz. Without co-ordinated image building, will the demand be there? The consequences of that not happening is not good for the industry who are having good times and achieving good prices now.

And as final thought: We have a way to go before we can flaunt the wealth of viniculture knowledge that exists in France, but I wouldn’t hesitate to describe British creative design and marketing as world leading. What a shame if our fantastic wines were simply out-marketed by the French.

For the full results of our research, you can find the presentation here. If you would like any more information about these reults, please get in touch.

Posted 14 August 2018 by Chris Bullick