BRAND ARCHITECTURE - WHY IT ISN'T WHAT IT USED TO BE

The best brands in the world are simplifying their architecture. Updated definitions and examples of brand architecture.

Is Brand Architecture still a thing? What’s it for? Who is doing it? Who is doing it well? And does it apply to smaller brands?

Owners and managers of smaller brands will have to bear with me as I will come to what this means for them. But in the meantime, let’s look at what the big boys have been up to.

What really surprised me looking for articles on brand architecture is that a lot of the brands that were seen as archetypical of a given architecture no longer are. So what’s happening?

Let’s take a comprehensive look at the present state of brand architecture.

First of all, what is brand architecture? Unsatisfied with all those I could find, I’d like to propose a definition.

DEFINITION: BRAND ARCHITECTURE

The way branding is applied to an owned collection of products.

Yes, it really is simple as that. If you cannot explain your brand architecture on a postcard-sized piece of paper, it is because it is more complicated than it should be. And it shouldn’t be complicated. Why? Because of the purpose of brand architecture.

BRAND ARCHITECTURE: PURPOSE

Here we need to remember our Byron Sharp. In How Brands Grow, Sharp teaches us that Brand building is largely about building two market-based assets: Physical and mental availability. Brands that are easier to buy have more market share. So how does brand architecture relate to this? Very few businesses have only one product. Many businesses themselves are branded. So as soon as a business has two brands it has a branding dilemma. Are the products two brands of a house of brands, two brands in a branded house, an endorsed brand or two-sub brands?

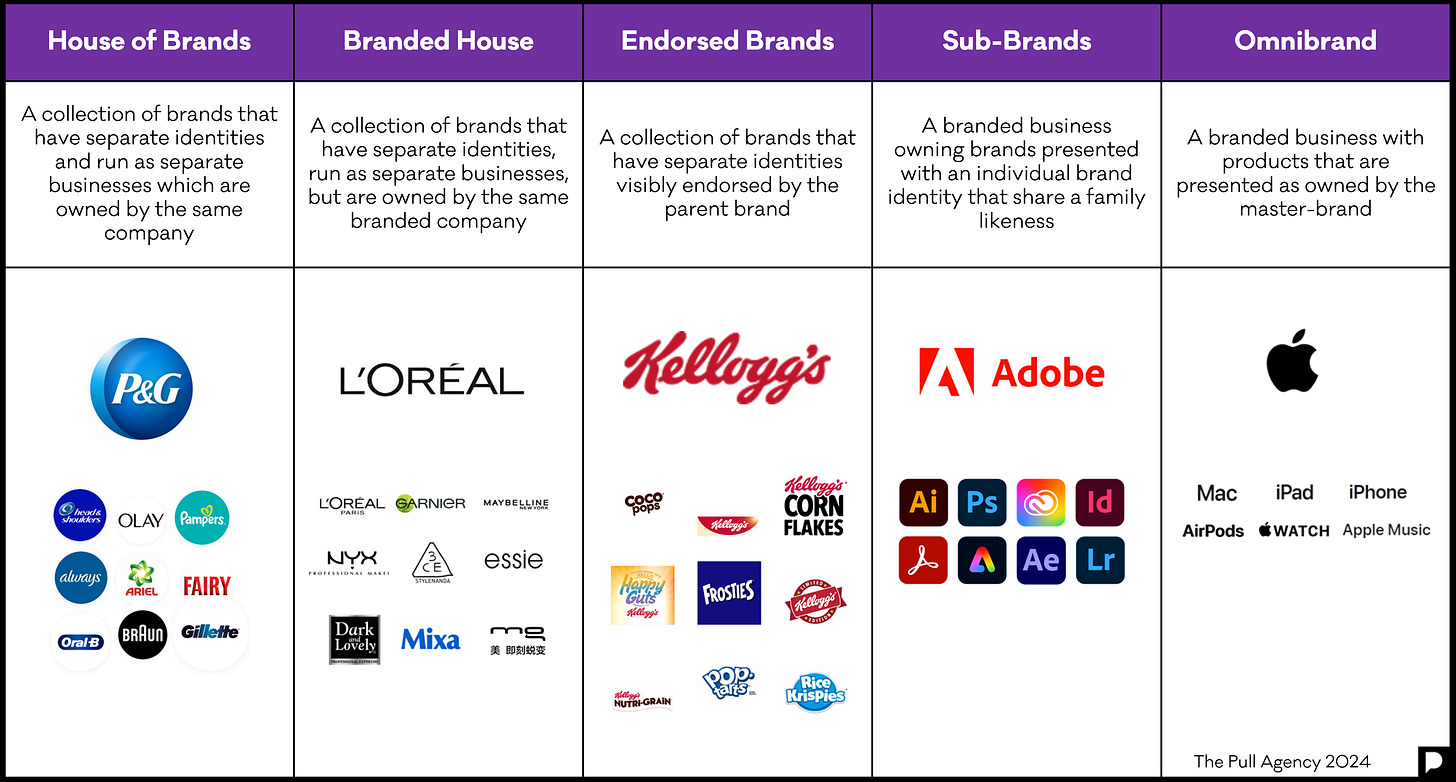

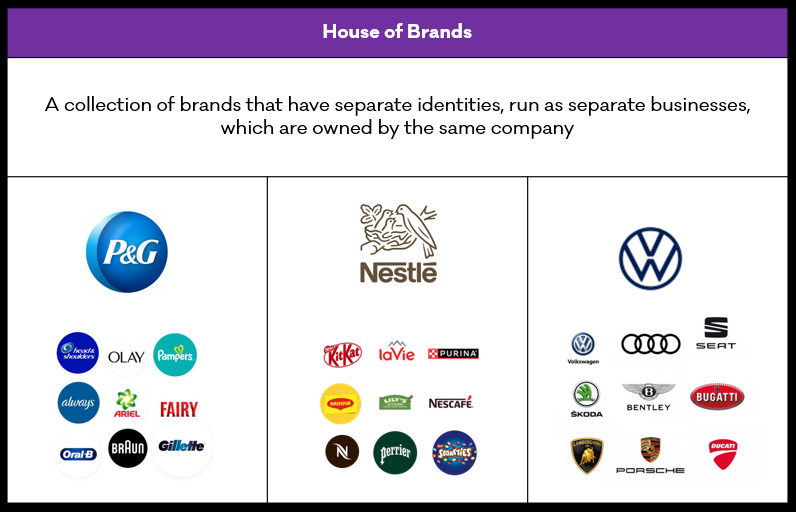

Confused? There is a widely-used model floating around depicting brand architecture that figures FedEx, Apple and Marriott as examples of Branded House, Sub-Brands and Endorsed Brands respectively. The fourth example is Procter & Gamble illustrating a House of Brands. This is the only example in my view that is currently correct. The others are wrong or outdated.

The route a brand takes should be driven by what will be easiest for a consumer (or B2B buyer, the same rules apply) to understand, navigate and remember.

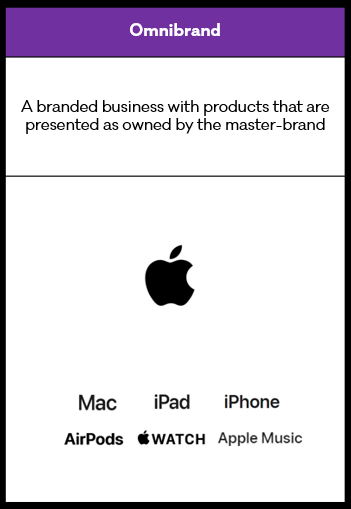

In terms of the conventional model referred to above, I would describe FedEx as now operating an Omnibrand architecture. Marriott is now just one brand of House of Brands Marriott International - who also now own Ritz Carlton and many individual ‘unbranded’ hotels and resorts. Apple in my view doesn’t operate a true sub-brand architecture, but like FedEx has become an Omnibrand. I would argue that Disney which is often depicted as an endorsed brand is now a branded house having bought ESPN, Marvel, National Geographic etc.

In reality there are subtle variants in the way businesses are organised within each of the five models I have identified. But these are internal and tend to relate to things like accounting and shared resources. I have taken a very pure brand marketing approach and only considered perceptions created by branding.

And in truth the distinction between house of brands and branded house in my analysis is only one. That is whether the company owning the house uses its company name as part of its branding and invests in advertising that brand. So unlike P&G, L’Oréal is both the company brand, and used on a large proportion of their products.

I think there are fewer examples of house of brands as a result of the Omnibrand phenomena. The best examples to me are these.

When I worked at P&G in the eighties and early nineties, I was on the side of an argument taking place at the time that P&G should update its 1882 logo and use it to endorse its brands. In the end its hand was forced, as the archaic logo was the subject of rumours that alleged the brand contained ‘satanic’ elements. An updated version was introduced in the early nineties, but the rumours failed to go away. So a new typographic logo was created As in the diagram above).

What waue back then and is true today is that most people buying P&G brands have never heard of P&G. The company is quite happy about that. What was discussed back in my day was whether there was a benefit in using the P&G logo to endorse their brands. At the time I was in favour of it, but I don’t think I would be today, and after a short period of P&G doing this, the reference has reduced down to the small print on the back of packaging. From a pure brand marketing point of view this makes sense.

Clients often ask “I’m launching this other thing. I’m not sure whether to create another brand for it.” The first thing I always respond with is: “OK, but remember running two brands will cost you twice as much as one.” This is the purist thinking behind P&G’s refusal to treat the business as another brand. Every brand in P&G is run under a separate P&L (although they now come together at the category level with a category manager and P&L to reduce wasteful intra-brand competition). I’m always amazed by how few marketing people know about this brand management model. In P&G’s view, spending money promoting P&G is a waste. You can’t ‘buy a P&G’ (other than shares and if you had you will have done very nicely), the brand has no revenue of its own, and market share cannot be directly correlated to physical and mental availability of P&G.

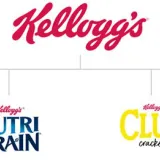

Unilever, almost always outperformed by P&G in every metric, better fits the Endorsed brands model, using the Unilever logo on most products and in advertising. This is at a much lower level than Kellogg’s though. You could argue this costs the brand nothing. But you could conversely argue that every inch of packaging or advertising real estate a brand gives over to it’s ‘house’, is giving away space that it could use to improve it’s own awareness. I may be biased, but I’m with house P&G.

Again, what I think is not always understood about the house of brands and branded house models is that while brands have to stand on their own and yield a profit to the house, they can share a lot things. These include brand management know-how and expertise (a high performing brand manager can be moved to a poorly performing brand), marketing methodologies, R&D, manufacturing, sales teams and channel relationships. All of these things reduce costs and add strength to the collection.

Coca Cola clearly meets my definition of a branded house:

“A collection of brands that have separate identities, run as separate businesses, but are owned by the same branded company.”

But they just threw a curved ball for me by running this ad featuring many of their brands.

It would be interesting to learn more about how the ad performs. System1 measured it as only ‘average’ for long term brand building. To me it feels reminiscent of the kind of deal a business like Coca Cola would try to do with a grocery retailer to get a display of Coca Cola products on an aisle end at a key time of year. But it’s interesting to see what a house of brands/branded house can experiment with.

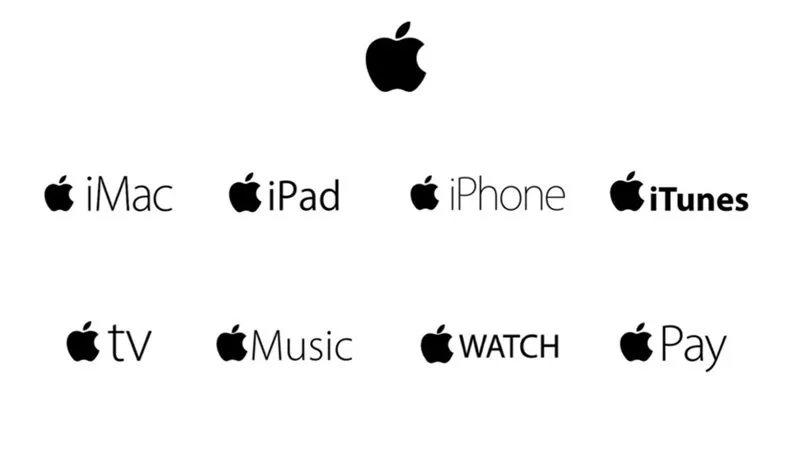

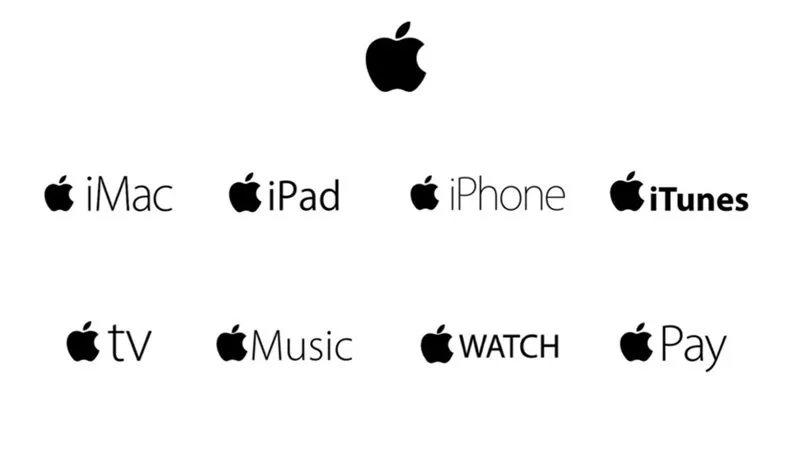

So what’s happening with the omnibrand thing? Well I think it’s the extension of the same logic. As we have seen, not so long ago Mac, iPad, iPhone were described as Apple sub-brands. But take a look at those products now. I would argue that Adobe’s products are sub-brands because Adobe has carefully created unique identities for each one. Apple on the other hand has evolved into an omnibrand where the products don’t really have their own identity. Surprisingly perhaps, this is the same logic as P&G use above. As with the house of brands vs. endorsed brand argument - why invest in marketing sub-brands when all the work can be done by one megabrand or omnibrand?

Besides of course, with a tech brand there is something else going on in the background. This is what in my other corporate career (At Motorola) we used to call the ‘walled garden’. More than any other brands, Apple operates as a walled garden. Offering superior operability across it’s own products, there is all sorts of encouragement to users to stay in the Apple garden. Generally speaking, you are either an Apple fan completely or not at all. The level of commitment from Apple users is generally at another level to competitors – even strong ones like Samsung. This reaches such heights that the only way to really accurately depict the fervour of many Apple brand users is to define it not as brand loyalty but religion.

This perhaps is the ultimate testament to the purest brand models exercised by arguably the two best branded business in the world right now - Apple and P&G - ruthless simplicity.

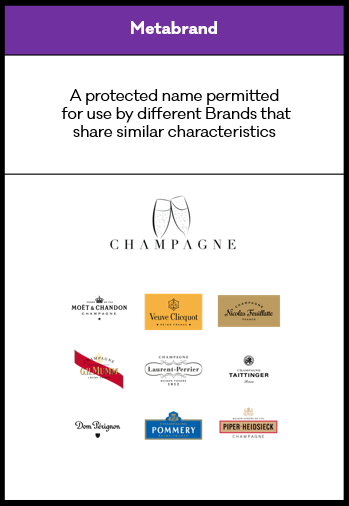

Before we finish on brand architecture, there is one more model that I have left off my new Big 5. We ‘discovered’ this at the Pull Agency when doing consumer research for the English wine industry. The question being posed was whether ‘English Sparkling Wine’ (largely directly analogous with Champagne in terms of production and grape varieties, every bit as good as the French product, some would say better) would benefit from a name like Champagne, Prosecco and Cava - from France, Italy and Spain.

We largely concluded that it would (as English Sparkling Wine was currently no more than a descriptor, and very poorly understood in the UK, let alone elsewhere). We determined in the process that a term like Champagne acted as what we called a ‘metabrand’.

The name can only be applied to wine produced in a limited area of France, and the protection has successfully been extended to cover wines produced elsewhere like Australia and the US. We identified the ‘brand essence’ of Champagne as being ‘the moment of celebration’. Our research suggested that all Champagne brands have an unwritten agreement to aim their advertising in a way that supports the values and meaning of the metabrand Champagne.

In my next blog I will interpret these definitions of brand architecture in the light of what it all means for smaller brands and smaller brand houses. Spoiler alert: Whatever the size of your set of brands - the same principals apply.

Posted 25 January 2024 by Chris Bullick