Thomas Cook – Financial disaster or brand disaster?

17 different brands, 21,000 employees, 22 million holidays sold a year, 550 travel agents, £150m debt interest paid last year and going down with a balance sheet deficit of £3bn. However you look at it, Thomas Cook was a big operation.

Seen by themselves as a ‘much loved British travel brand’, how good was Thomas Cook’s brand management? Was Thomas Cook a good brand brought down by hubris and poor financial management? Or did poor brand management contribute to, or even eclipse the financial mess?

Taking a retrospective view of Thomas Cook’s brand management is already quite tricky. The administrators (I assume) have acted swiftly to take down their website, YouTube and other social media channels. This might now be standard operating procedure after a failure to do likewise at HMV left a sacked and disgruntled social media operator with the keys to the brand’s Twitter account – which he made full use of for a day.

So no Tweets or Instagram posts remain, although their Facebook page does. This shows 750k followers which isn’t a bad number however you look at it.

Standing back to look at the UK travel market, the first surprise is how big the package holiday market still is. I for one would have thought the impact of the web in undermining the package holiday model would have been more dramatic. After all, the relentless rise of low-cost airlines and Airbnb must mean they are taking business from somewhere.

In 2000, 55% of all holidays sold in the UK were of the package variety. By 2016 that was 40%. And judging by the number of travel agents still clinging to the high street, there are still a lot of people whose annual trip to the sun still starts with a conversation with a travel firm rep.

But it’s difficult not to think that Thomas Cook were over-represented offline. While their 2007 merger with rival MyTravel had only added more of the same in terms of package holiday customers (and added more debt – and later a write-down on the basis they had overpaid for MyTravel), merging travel shops with the Co-op in 2010 looks in hindsight like a move Thomas Cook should have resisted. Starting out as a joint venture, the Co-op pulled out in 2016 leaving Thomas Cook with hundreds more travel shops while the market moved steadily online.

So if Thomas Cook was over-exposed offline and to low margin mass-market package holidays, what about the role of brand management at the company? Then CEO Harriet Green said in 2016 that “The reality was I knew a lot about transformation, a lot about restoring brands and transforming to the web.” This was after she hit the news for successfully raising £1.6bn in new equity and bonds. This undoubtedly helped keep the show on the road for a while, but the claims about brand and digital transformation look a bit hollow now.

But could better brand management have saved Thomas Cook from their current ignominy?

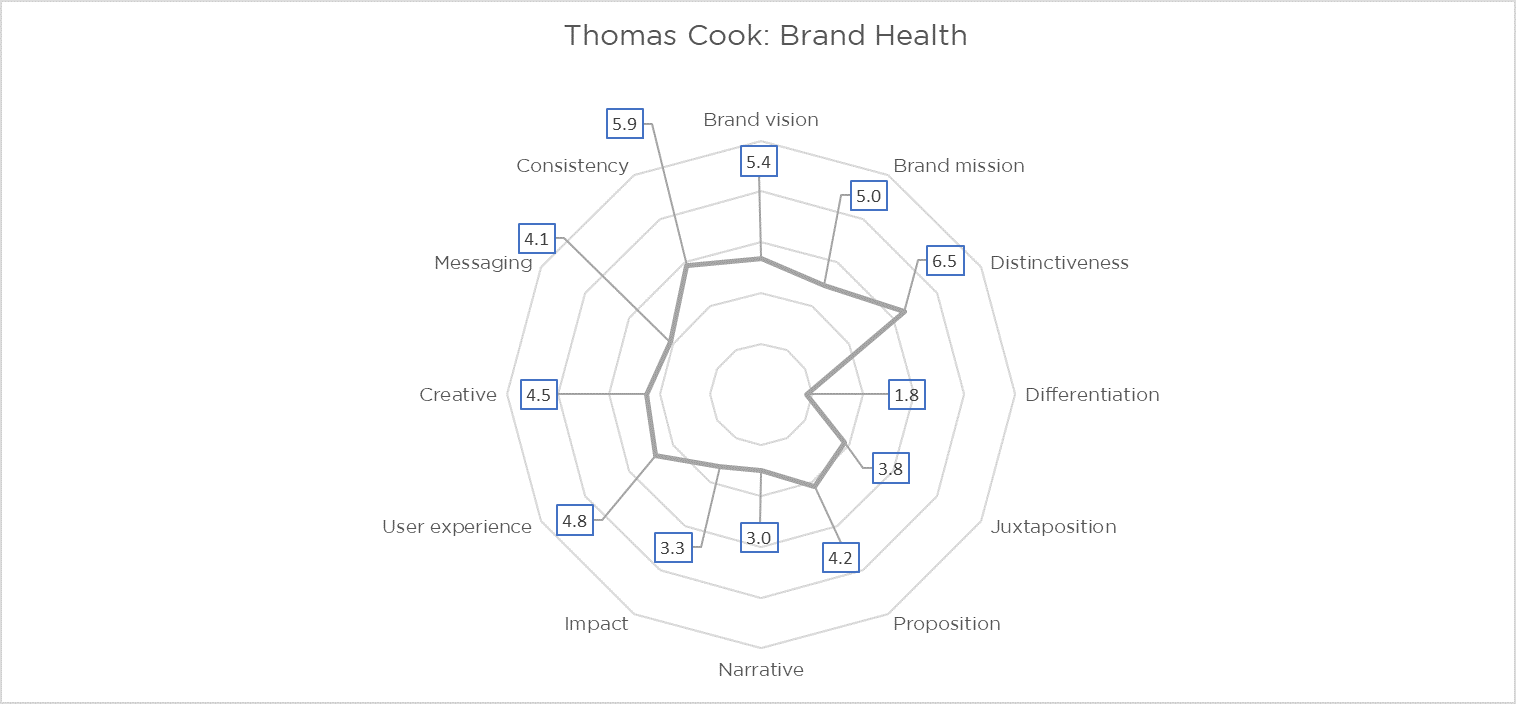

Pull put the brand through the ‘sausage machine’ of our Brand Healthcheck™. The result is below.

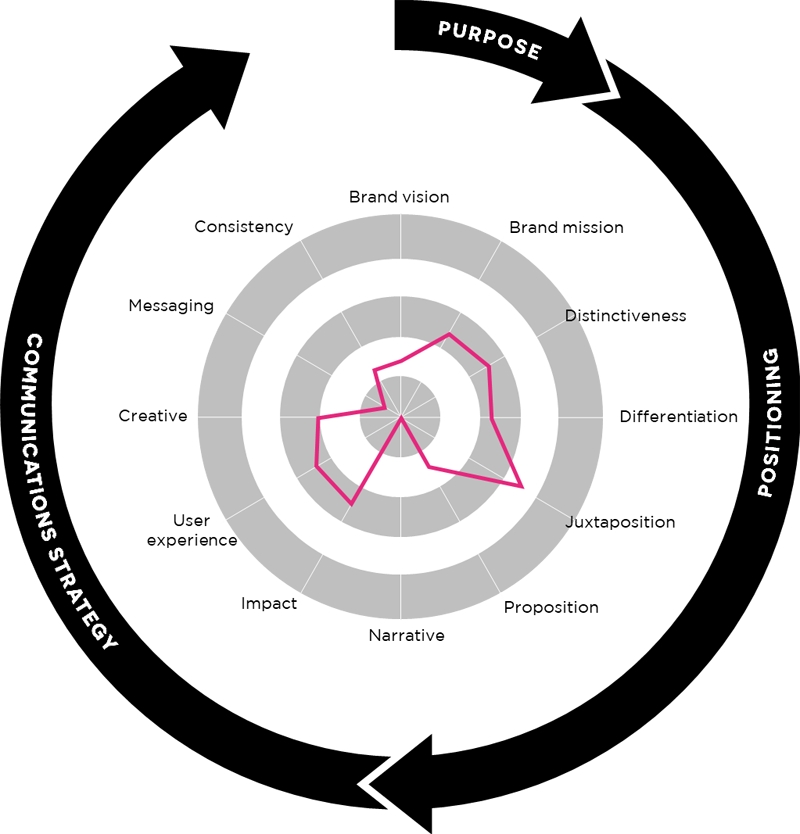

The approach is based on the Pull Agency’s Brand Blueprint™ model.

Pull’s Brand Blueprint™ helps brand owners develop their brand by following a sequence that starts with Purpose.

A Brand Healthcheck™ assesses the achieved state of a brand by evaluating each of the dimensions above against weighted criteria. This then acts as a kind of proxy for brand equity. In the absence of known awareness or consideration measures (which are typically not available for many of the mid-size brands that Pull works with) it gives brand owners a reasonably objective basis for the effectiveness of their brand management over time.

Here’s where Thomas Cook came out:

Their total brand score was 52/100. This is low for a major brand. There were no really strong scores and they scored particularly low on differentiation. We have seen lower, but lower scores we have met have always gone hand-in-hand with strong operational and financial performance – in other words, they represented an opportunity for a strongly performing business to perform better by investing in brand. In Thomas Cook’s case there appears to be a deadly coinciding of poor financial and poor brand performance.

Thomas Cook expressed a desire to be “The world’s best loved holiday company”. However there is no discernible link between that desire and the brand experience. They also defined ‘Care’ as a chosen ‘key differentiator’. Yet even before the collapse unfolded they had a Trustpilot score of 2. The company had also earned opprobrium in 2015 after being found to have ‘breached their duty of care’ following the deaths of two children from fumes off a faulty heater at a hotel in Corfu. Thomas Cook CEO Peter Frankhauser exacerbated the situation by saying that the company had “Nothing to apologise for”.

Perhaps choosing ‘care’ as a core value happened later, and was a reaction to the negative perceptions, but it seems in retrospect that such a gulf between stated brand purpose aspirations and reality implied a brand deficit that was just as big as the financial one that eventually overwhelmed the business.

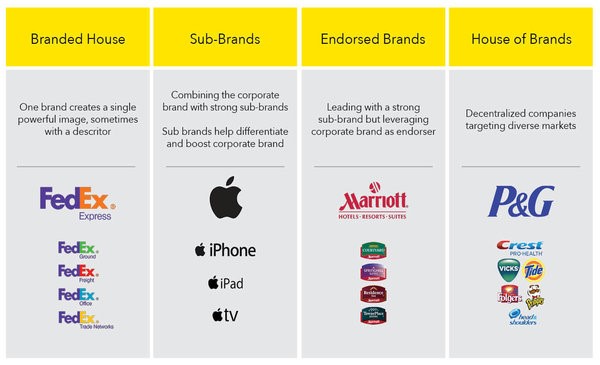

The other striking thing about Thomas Cook was that it was really a house of brands. Looking at past pronouncements on marketing by the company, they always seem to have been made by a ubiquitous ‘Marketing Director’. They had 17 brands! If they had adhered to classic brand management practice as invented and conducted by the likes of P&G they would have had 17 brand managers. Each would have been responsible for the P&L, R&D, marketing and performance of their brand. Brands that didn’t meet the portfolio criteria would have been divested of, and those that did would have been organised into categories to leverage synergies between brands and strengthen the company’s position in key categories.

While we are sure that brands like Sunprime and SunConnect almost certainly had marketing personnel, there is no evidence that Thomas Cook had anything like the disciplined approach to brand management that the best house of brands companies have.

So overall, Tomas Cook’s weak brand management seems to have contributed hand in glove with what - underneath the bravado of successive bosses - actually amounted to ‘Keep borrowing money and carry on’.

The business was caught in a pincer between wafer-thin margins that weak brands deliver and high interest debt. There are sound businesses that lack a strong brand, and there are strong brands that are highly geared with debt. What Thomas Cook shows is that big debt and a weak brand are a recipe for the inevitable.

Posted 30 September 2019 by Chris Bullick